Assessing the Effectiveness of PMs

Part 1 of pmcurve Series: Assessing the Effectiveness of PMs and PM Roles

For the new ones here — 8,000+ smart, curious folks have subscribed to the growth catalyst newsletter so far. If you are new here, receive the newsletter in your email by subscribing 👇

You can read 50+ posts from the past here - https://www.growth-catalyst.in/archive

Good Morning,

It has been a long time since Growth Catalyst arrived in your inbox. There are many reasons for that; part of the reason is that I couldn't find an excellent series to write about after finishing Growth. I have found something I am excited to write about.

I have been talking to PM leaders and entrepreneurs, and one of the key problems I see is that many PMs are ineffective in their roles. A lot of PM roles have been reduced to glorified project manager roles.

This is a tall claim, and I wouldn't take people's word for it. One thing I know for sure is that if there is any such thing, it's not all PM's fault. The ecosystem we live in has a lot to do with it. The company culture and what we are rewarded for, shape our jobs. What's more, we have the first generation of tech entrepreneurs and leaders in India. They are still learning and figuring out how PM fits into the Indian tech ecosystem.

So why not take a step towards understanding the problem? Once we have understood, the solution becomes relatively easier. That is where the series comes in.

Here are six parts of this series:

Assessing the Effectiveness of PMs

Necessary Skills to Enter PM/ Cracking PM Interviews

Necessary Skills Required to be an Effective PM

Sufficient Skills Required to be an Effective PM

Becoming an Effective PM Manager

Managing PM managers (Director/VP)

To understand it well, I am also doing 1:1 with seasoned product leaders, PMs, and entrepreneurs. You can share your thoughts at dpak1907@gmail.com, and I might reach out to discuss it further.

Let's start with the first one — Assessing the Effectiveness of PMs.

If you are a PM who doesn’t come from a software background, you can checkout my book ‘Tech Simplified for PMs and Entrepreneurs’ which has been immensely useful (readers’ word, not mine) in getting them to understand tech well :) 240+ people have rated it 4.5+ on Amazon.

The Leverage in a Role

You may be familiar with the quote of Archmedes: "If you give me a lever and a place to stand, I can move the world."

Archimedes was a mathematician, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, among many things. He understood the importance of levers around how they give mechanical advantages to moving an object.

Levers are how you can accomplish 10x, 100x, or 1,000,000x what others can. The word leverage is 'the act of using a lever to move something. But how does it apply to the world of business and product management?

Walmart Founder Sam Walton opened his first store in Bentonville, Arkansas, in 1962. Saturday is the most important retail day of the week because shoppers often come to stores on weekends. Sam worked every Saturday to demonstrate to his employees that if they had to work on Saturdays, then so should he. In fact, he showed up by 3:00 AM to review the ledgers and determine what adjustments needed to be made in order to enhance sales.

He also started the tradition of Saturday morning meetings at 7:00 AM by the top management of the company, which endures to this day after 60 years. Aptly named, the meetings took place on Saturday mornings and ran for about 2.5 hours. He thought it was unfair for store associates to be working on the busiest day of the week and not management. In his autobiography, he wrote, "If you don't want to work weekends, you shouldn't be in retail."

David Glass, the Former Walmart CEO, said that by the time competitors received their sales numbers on Monday, Walmart had made changes. The Saturday meeting gave Walmart a competitive edge.

The 7 AM Saturday meeting is an example of a great lever to shift company outcomes.

It sets the ritual of reviewing numbers and making decisions basis them before the critical event, not after them. The advantage against competitors who review on Monday would keep accumulating.

It helps boost the morale of retail associates who have to work weekends. Better morale → more happy associates → better customer service

The managers who don't want to spend some time on weekends working would eventually move out, leaving the ones who believe in the cultural norms.

Culture is an excellent lever for any business to grow. Setting the right culture through rituals is the highest leverage activity a founder can do because it has ripple effects.

Now that we have understood what leverage is in the business context, let's look at what affects the leverage of a role.

What Affects the Leverage of a Role?

PM is a high-leverage role for an org. That's why some also refer it as 'the CEO of the product.' The output of tens of engineers and designers depends on the insights and decisions taken by a PM. The risk and reward attached to this role for an org are very high. The leverage is even higher when it comes to startups because a miscalculation can cost a startup's survival.

The product manager is also a generalist role. And as happens with generalist roles, everyone believes they can do such roles effectively. That's not the truth, though. If you work long enough in this role, you end up realizing that there is a distinct set of skills that you need to do the job effectively.

A problem that has occurred in the Indian tech ecosystem is that PM has converted into a low-leverage role in a lot of places. To understand why it has happened, we have to deconstruct the leverage of a role first.

There are three key factors that define leverage associated with a role:

Authority

Compounding Ability

Variance of Impact

Let's understand them one by one.

Authority

The simplest way to understand high-leverage roles is through a lens of authority. The CEO is a high-leverage role since a decision taken in that position moves the entire org in a particular direction.

On the other hand, an analyst preparing pre-determined weekly reports isn't a high-leverage role because what the analyst does most of the time doesn't move things. What's more, the analyst doesn't have the authority to change things unless the person at the top agrees with the recommendation.

Compounding Ability

Industrial-era roles were mechanical. If you could lift 100 bricks a day, the ability didn't improve drastically over time unless you have a lever ;)

The tech world lives in the knowledge era. The ability in the knowledge era roles compounds over time. Because knowledge has a compounding effect, your ability to do specific roles improves over time.

But it doesn't apply to all roles in the knowledge era. Think of the weekly report analyst. Since the analyst is doing a well-defined job every week, the ability doesn't compound.

Replaceability is a useful lens to filter the roles with compounding ability. Replaceability was very high in the industrial era, where you could pick up fit men/women to do a day's work and pay daily wages.

Weekly report analyst is an easily replaceable role. The role definition is so clear that you can hire someone else easily. A CEO role, on the other hand, isn't easily replaceable. You see strong CEOs coming back again to help steer the companies in the right direction. Howard Schulz returned as CEO of Starbucks in 2008. Bob Iger is making a comeback to Disney this year.

Variance of Impact

The variance of impact can be assessed by asking a simple question — can two people in the same role have widely different impacts?

The weekly report analyst isn't a high-variance role. The CEO is a high-variance role.

Assessing the Leverage of the PM Role

Let's look at how the various factors affect the leverage of the PM role.

Authority: PMs usually have good authority around decisions in the areas they manage. One of the critical expectations in this role is to define the strategy and roadmap of the product.

PM is low-leverage if they don't have the authority and freedom to define the strategy and roadmap.

PM is high-leverage if they have the authority and freedom to define the strategy and roadmap. In big tech (FAANG), this freedom increase over time as you grow to more senior levels.

Compounding Ability: The most critical ability of a PM is the product sense. The product sense is the ability to come up with the right, creative solutions to user problems. It depends on domain knowledge, user knowledge, and UX problem-solving skills. Product sense is hard to replace because the ability improves as you spend more time in a market and on a product.

PM is low-leverage if the PMs don't have the learning aptitude to improve their product sense.

PM is high-leverage if PMs improve their product sense over time.

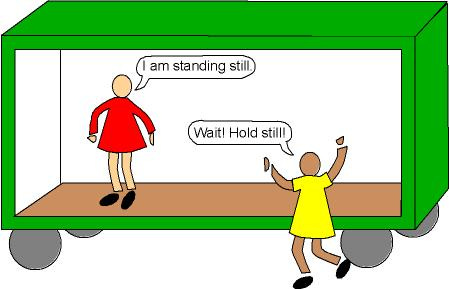

Variance of Impact: Two people managing the same product can take it in widely different directions.

Conviction to set the right direction makes PM a high-leverage role.

Lack of conviction results in a low-leverage role.

In my experience, I have seen organizations with both high- and low-leverage PM roles. Usually, we can answer this by looking at these conditions.

Orgs with high-leverage PM roles have a high degree of freedom. The PMs operate with high learning aptitude and conviction.

Orgs with high-leverage PM roles have a low degree of freedom. The PMs operate with low learning aptitude and conviction.

The learning aptitude and conviction are person-specific. Even with learning aptitude and conviction, PMs can still fail if they lack the authority and freedom to operate.

Let's assess what caps degrees of freedom.

Degrees of Freedom

Because PM is a role that has such high risk and reward associated with it, the founders/ top executives often try to take control out of fear. It leads to a low degree of freedom for PMs. The lack of freedom almost always leads to a linear impact because they can't add a new idea based on a hunch/insight they believe in.

The best thing you can do in the absence of freedom is to execute well, which has immense value for any organization. After all, (1)^n is 1, whereas (1.2)^n keeps growing. Being fast is a competitive advantage in itself.

But this is true, keeping all things equal. When you lose degrees of freedom, you lose collective product sense (the product sense of a group). Steve Jobs said it best in an interview,

Digging faster in the wrong direction only takes you faster to the wrong destination. Collective product sense helps you course correct quicker. So even if you are a bit slow, you end up reaching the right place. Look at all the examples of bootstrapped unicorns — Basecamp, Mailchimp, etc. who took their own time to build the right thing over decades.

Another important point to note is that when the best PMs lose freedom, they end up going to other places where they can find that. Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon have been able to build multiple big businesses because they can hire people who can see beyond what founders can see and chase that.

David Leib, the product lead for Google photos, recently told in one of his interviews on 20VC that he was asked to leave the Google photos team early on because his vision for photos didn't match that of top executives. He wanted to build a personal photo management tool, whereas others wanted him to build on top of Google+. He came back after convincing Google founders to do it his way, making Google photos successful today, whereas Google+ sits in the Google graveyard.

One of the common reasons for low freedom that I hear from leaders is that an org starts with giving enough freedom, and because the first few PM/PM leaders weren’t effective, they stop giving this freedom. Whatever the reasons may be, you as a product leader or founder need to assess the them carefully and objectively and whether they are helping or hurting the company.

It’s impractical to ask leadership straightaway to give freedom for multiple reasons. The way to solve the low-leverage problem is to objectively measure PMs effectiveness, and provide them more freedom over time. But how do we measure a PM’s effectiveness?

Measuring PM’s effectiveness

Let’s take software engineering as an example. It’s quite objective to measure the quality of code a software engineer writes. You can differentiate between a good, a bad, and an excellent coder because there are quantitative measures of performance in software engineering. For example, if the same webpage built by engineer X takes 100 ms (p90) to load, whereas the other built by engineer Y takes 1000 ms (p90), you can be reasonably confident that engineer X knows better when it comes to webpage speed optimisation.

For PMs, such objective measures don’t exist. Why is that? Three reasons — long feedback cycle, hard-to-measure recall on decisions, and faulty frame of reference.

Long Feedback Cycle

PMs often come up with ideas, validate them with consumers, and then work with designers and engineers to ship them. Whereas the code of the page built by one engineer can be reviewed by others and made efficient quickly, the feedback loop for a feature proposed by a PM takes months to close.

Hard-to-Measure Recall on Decisions

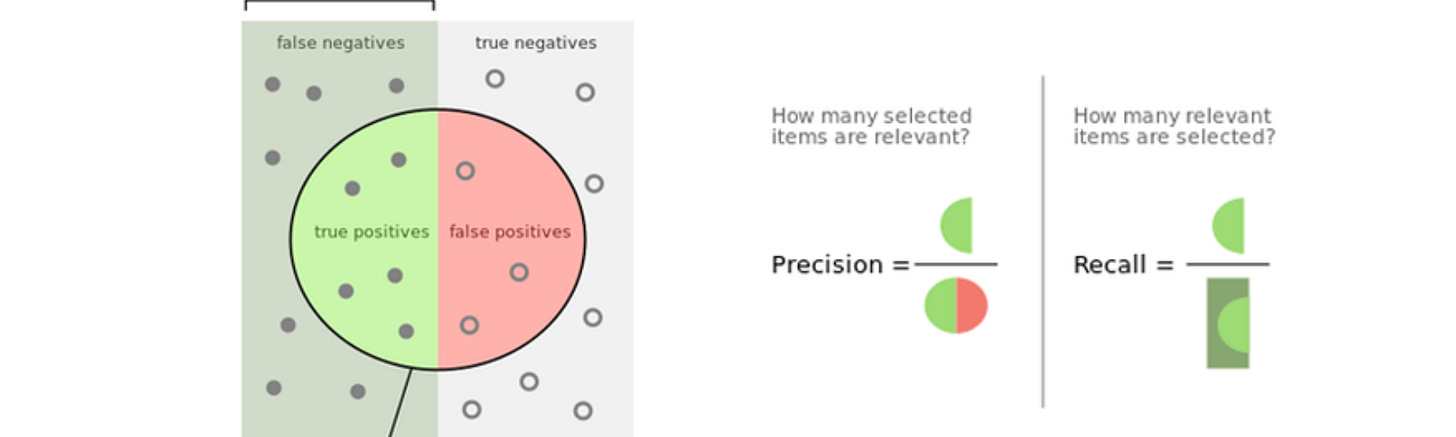

In data science, there is a term called ‘recall’ used to measure the effectiveness of models. Recall is equal to (positives a model captured) divided by (total positives) in a dataset.

In terms of the PM's role, recall can be defined as — if a problem has N good solutions, what % of them were evaluated by the PM? Usually, the exhaustiveness of solutions helps you arrive at the right decision.

You can test various models in data science and compare their recall. It’s very hard to measure a recall score of a product decision as we can’t test all ideas within a reasonable amount of time and come with this score.

Faulty Frame of Reference

If the leaders who are measuring effectiveness don’t have a strong product sense, they can’t gauge the product sense of PMs in the team. They end up measuring their effectiveness through whatever they are good at or their definition of the role is.

I would call it measuring through a faulty frame of reference.

Such fundamental attributes of the role result in two large problems:

At an organisational level, PM evaluation becomes subjective. This is why there is a varying degree of leverage PMs have in different orgs.

At an individual level, PMs find it hard to charter a growth path for themselves. They end up learning whatever the organisation over-indexes on, and can’t do the PM job effectively.

These problems need to be solved both for the organisation and the individual. The next set of articles will help you assess yourself as a PM, and also your org as a top executive/ entrepreneur.

See you next week,

Deepak

Thoughtful and thought provoking. Simply Loved it!

Apart from PM insights, I learn a lot about storytelling as well from your articles.

Waiting eagerly for the next article :)

Addresses some critical points

For the longest time we have built things with no PMs and then have recently made our first PM hire. This gives a sense on how to navigate this critical relationship