4,500+ smart, curious folks have subscribed to the growth catalyst newsletter so far. If you are new here, receive the newsletter weekly in your email by subscribing 👇

Dear Reader,

It has been a month since my last post. Few readers reached out to ask whether I would continue writing. The worry is understood — many aspiring writers start dreading writing once the initial romance with the idea of writing starts wearing off. You can expect regular posts hereon because 10 months in, I am still in love with writing.

Before we get to the post, I request you to spend 2 mins on this survey form. This is very important for readers as the survey will help me create the writing roadmap this year. I got this suggestion from a good friend, Kali who is also a regular reader of my posts, thank you 🙏🏻

Enough chit-chat; let's get on to the post.

The retention of the product is a function of the user's repeat behavior, also called habits. Almost all of us have tried to build healthy habits by signing up for gym memberships or otherwise. Most of us also failed. The outcome shows that repeat behaviors are the hardest to form, which makes retention one of the hardest problems to solve.

Luckily, there are ways to manage and improve retention. I have already written a post around frameworks to fix retention. If you haven't read the post, I would recommend reading it. The post covers Fogg's behavior model, super apps, and hooked.

This post is primarily an extension of that post. We will cover

How habits get built

Switching costs and why they are so powerful in creating habits

Time as an added dimension to Fogg's behavior model

The Science of Habit Building

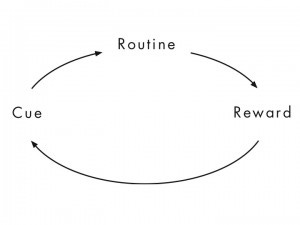

Many years back, I read the book The power of habit by Charles Duhigg and absolutely loved it. Duhigg wrote about research done around habit building at MIT in the book. The researchers discovered that a simple neurological loop exists at the core of every habit, consisting of three parts: a cue, a routine, and a reward.

For example,

Cue or trigger — getting bored

Routine or action — opening Instagram

Reward — seeing the likes on your post, new photos from friends

The loop keeps repeating day after day every time you see a cue/trigger.

Researchers further realized that when the rewards are variable, i.e., they change every time you do the routine, the habits are more strong. It's like you opening Instagram multiple times after submitting a photo because you can't anticipate the # of likes and keep seeing different # of likes (variable rewards).

If you wonder why variable rewards create stronger habits, it has to do with what happens in your brain when you do the same action and experience variable rewards.

When the brain gets an unexpected reward, it releases dopamine. On Instagram, the momentary rewards come from the likes, comments, good photos, etc. But we can't predict the size of the reward nor the frequency of the reward. This means that you get a dopamine hit every time you open Instagram. Over time, you develop a dopamine dependency and keep coming back for the dopamine hit. For that reason, we get addicted to social media.

Another industry that employs variable rewards is casinos. Throwing dice and getting unpredictable monetary rewards gets gamblers addicted. They want to get the dopamine hit again and again, and that drives them to casinos.

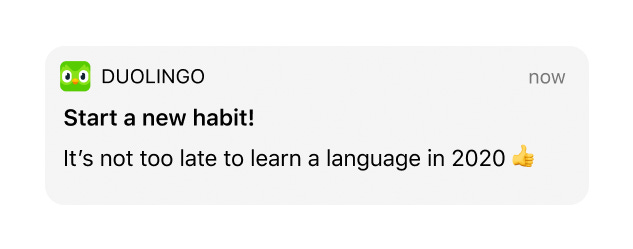

How exactly do products use the science of habit building? We have read/talked about how social media uses the habit science to get people addicted. Let's talk about something different. From the Duolingo blog,

In January 2020, we tested three push notifications to encourage learners to make language learning their focus for the year. The winner?

That beat out "Reach your goals! Keep your resolution going with a lesson."

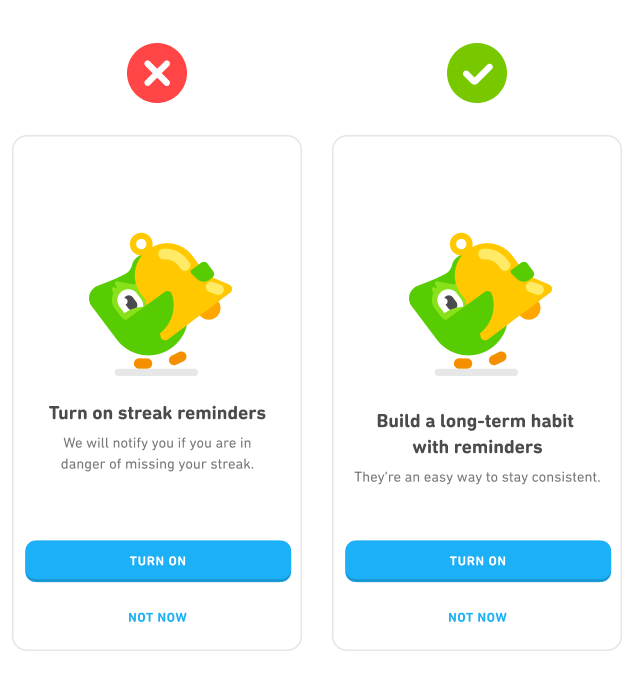

"Habit" also makes a difference in how learners receive those push notifications. Duo reminds you to practice — but only if you ask him to. Previously, the opt-in screen below focused on getting reminders in order to keep your streak, but when we tested copy around building a long-term habit, 5% more learners opted in.

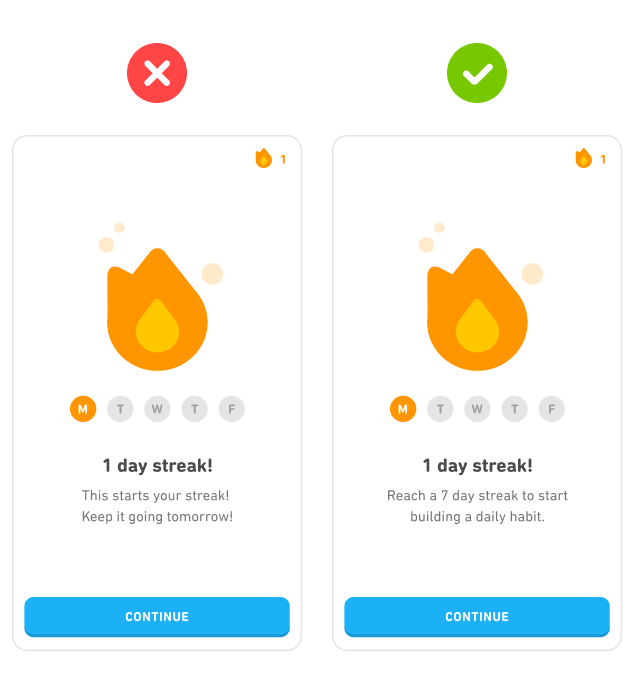

Finally, there's the screen after you complete your first lesson. (Way to go!) After celebrating this milestone, we encourage learners to come back for more. Previously, this screen said "This starts your streak! Keep it going tomorrow!"

But when we tested "Reach a 7 day streak to start building a daily habit," learners came back in greater numbers. That’s what I call a win-win — and the start of a strong habit.

The cue in Duolingo could be a push notification, someone speaking in a different language, etc. The routine is opening the app and completing the lesson. The reward is creating or maintaining the streak.

Is there a way Duolingo introduces variable rewards and even creates a stronger habit loop? It can do that by making learning a social construct.

An app that does that well is Strava. Strava is a fitness app. You can add your social circle on Strava and see the fitness activities they are logging in your feed. You can give them likes/kudos for that. Over time, people would come back to see who gave them kudos and also keep doing physical activities to create a better social image.

If you are building a B2C product for daily/weekly usage, think about your product's cue-routine-reward loop. If not, wait for the next two sections.

Switching Costs

Switching costs play an important role when the product solves a particular need, and multiple products solve the same need. Switching costs ensure that the users, once acquired, will keep using your products and won't switch to your competitor.

One of the strongest switching costs is the network effect that we frequently see in social apps. As the network of your friends grows in a particular network, it's hard to leave it. Think WhatsApp, Insta, Snap, FB.

Beyond social products, other apps build switching costs differently. There are many different ways to build switching costs. If you need a framework to think about it, you can think about four factors — time, effort, psychological, money. A combination of these 4 creates switching costs. Here are some examples:

Data: Leaving one platform for the other forces users to let go of data or activity. Users don't want to lose that, and that creates a high switching cost. Depending on the use case, data can hit high on time, effort, and psychological factors.

If you switch from Spotify to another music app, you'll lose your playlists.

Android or Apple users will have to give up their purchased music tracks, apps, or movies if they want to move to another platform.

Learning Curve: If there is a learning curve for a product line, users will find it hard to switch to another product. It often happens with complex, enterprise products. The learning curve hits high on time and effort factors.

Salesforce is a prime example of this. Teams once learning how to operate with Salesforce find it hard to switch to another software.

Brand/ Industry Standard: This one takes time and happens in both B2B and B2C companies. It hits high on psychological.

In the 70s, the early IT industry projects often exposed decision-makers to the chance of losing their jobs because they would be held accountable for failure. Since IBM's size and quality in those days would guarantee a project's outcome, it seemed a logical, safe choice to go with the giant. Hence, the quote "Nobody ever got fired for choosing IBM" got popular.

In B2C, Apple is a great example of it. Apple means premium and quality to a lot of users.

Exit costs: If the customer wants to exit the contract before time, he/she has to pay early termination fees. Telecom operators such as AT&T or Verizon used to charge up to $350 in early termination fees. Over time, most major carriers have eliminated the 2-year contract for consumers, so early termination fees (ETF) are quickly becoming a thing of the past. Exit costs hit high on the money factor.

This is also seen in enterprise software where salespeople push for annual contracts, and there is a termination fee. It's no customer-friendly, and new-age SaaS subscription models are removing that.

Social Status/Influence: The rise of the Influencer industry has led to another major addition in switching costs. Once you have made your mark on a platform, you don't want to leave the platform and risk losing it. Examples — followers on Twitter, subscribers on YT, etc.

Time as an added dimension to B=MAP

I wrote extensively about B=MAT in the post, Simple Frameworks for Fixing Retention

From the post,

Let’s start with the basic question — what causes a particular behavior? The model that explains it is developed by BJ Foggs, who built the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University. He and his team research human behavior and how you can influence it to achieve business goals.

The Fogg Behavior Model shows that three elements should converge simultaneously for a behavior to happen: Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt. When a behavior does not happen, at least one of those three elements is missing.

With ample motivation and ability, the prompt/trigger shapes our behavior.

Once we start applying B=MAP to affect user behaviors, it becomes easier to find ideas of growth, conversions, etc. However, we often miss one important factor that affects retention most — time.

Motivation, ability, and our response to triggers change over time.

Take the example of MOOCs — the completion rate for MOOCs is quite low. Here is what the MIT research study around it says,

One of the big knocks against MOOCs since their beginning was the low rate at which students completed the courses, even as defenders pointed out that many students took MOOCs for knowledge or edification, rather than for a credential. The critique stuck nonetheless.

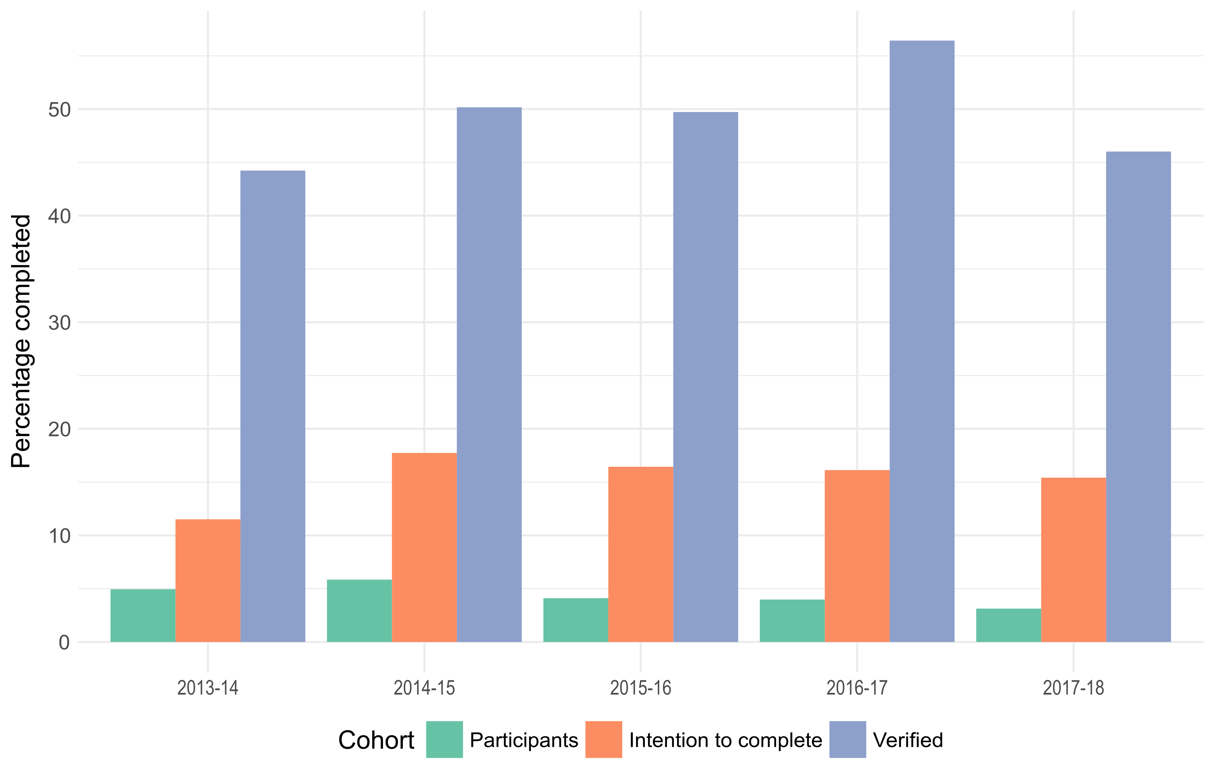

Among all MOOC participants, 3.13 percent completed their courses in 2017-18, down from about 4 percent the two previous years and nearly 6 percent in 2014-15.

If we think about it, MOOCs have solved the ability problem. You can attend a MOOC any time, anywhere in the world, as long as you have a smartphone/laptop. People also have ample motivation to learn something that can help accelerate their careers. Once you start the course, MOOCs also send you timely notifications. So why is the completion rate so low?

Because motivation and ability vary over time, so a typical graph of mine used to look like this during my college semester.

Can MOOCs solve the problem? Yes. One simple way was to add payment and certification, which increases the students' motivation to complete. Among the "verified" students, 46 percent completed in 2017-18, compared to 56 percent in 2016-17 and about 50 percent in the two previous years.

Another way is to make the course limited time. A limited-time course creates a sense of urgency throughout the course. This is a reason why cohort-based courses are picking up. A live classroom with a community and limited time to complete has better completion rates. Add to that high fee the cohort bases courses charge makes exit costs high.

Throughout the user journey, we should be on a continuous lookout to add motivation, ability, and prompts over time. Solving it for once won't be enough.

With this, I will wrap up the post. Before you go, please fill this survey if you haven't already.

Thanks,

Deepak