Uber and The Practical Aspects of Sizing the Market

Operating Well as a PM

👋 Hey, I am Deepak and welcome to another edition of my newsletter. I am currently writing two long-ish series of blog posts:

Product Interviews

Operating Well as a PM

I have previously written a long series (42 posts long) on Product-led Growth. You can get it in the email when you subscribe, or can find it on the newsletter home page.

10,000+ smart, curious folks have subscribed to the Growth Catalyst newsletter so far. To receive the newsletter weekly in your email, consider subscribing 👇

Let’s dive in the topic now!

When it comes to sizing the market, even experts make mistakes while doing the exercise.

Back in 2014, Uber raised a large round of $1.2 billion, valuing the startup at $17 billion. There was a big debate between Aswath Damodaran and Bill Gurley on Uber’s total addressable market and valuation.

Aswath Damodaran is a Professor at the New York University, where he teaches equity valuation and corporate finance. He has written several books on equity valuation, corporate finance and investments. Bill Gurley is a seasoned (and reputed) venture capitalist and a parter at Benchmark Capital. He was an early investor and board member at Uber.

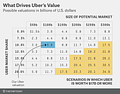

The debate around the valuation of Uber started when Damodaran wrote his analysis piece which valued the company at about a third of that value ($6 billion). Damodaran is a guru in valuation, and so the investor and startup community paid attention to this piece. He argued that since the total taxi market was capped $100 billion, Uber’s valuation at a 10% market share couldn’t be more than $6 billion. Even at a 20% market share, Uber couldn’t be more than $12 billion. He published a table around various scenarios, and what sort of valuation it led to.

Bill Gurley wrote a piece responding to Damodaran’s analysis of potential market size. He talks about a key mistake that people make when it comes to market sizing an innovation — an innovation can change how the market behaves, and measuring the market size on current behaviour isn’t correct! So sizing the market of Uber on the back of taxi market is also not correct.

He further talked about how Uber can be a car ownership alternative, and the size of car ownership market is pretty high as compared to taxi market.

“Uber’s potential market is far different from the previous for-hire market precisely because the numerous improvements over the traditional model lead to a greatly enhanced TAM. Now we consider Uber-like services as a car ownership alternative. This trend is just beginning, but because of the points highlighted herein, we believe this to be a real opportunity. For our model, we assume that Uber-like services will encroach on a mere 2.5%-12.5% of this market. This represents a potential opportunity of $150-$750 billion depending on how aggressively one believes these services can succeed as a car alternative.”

It has been 10 years since the debate, and it begs the question — who is proving more correct 10 years down the line?

Uber’s current revenue is $32 billion, and it is valued at $150 billion. But here is the catch — while it may look like Bill Gurley was more correct, part of the reason for such high revenue and valuation is Uber’s entry into an entirely new market — food delivery through UberEats.

Guess the size of ride-hailing market? $150 billion

Guess the size of food delivery (including grocery) market? >$1000 billion

UberEats today contributes to more than 30% of current revenue, despite being available in limited countries. That significantly expands the TAM of Uber, and lends to it’s current market valuation. Had Uber not entered this new market and stayed in taxi + alternative car ownership, Damodaran would have been more correct.

What Can We Learn?

So what can we learn from this case? One, it’s hard to predict the market size, especially for the Internet companies!

And there are two reasons for that.

First is what Bill Gurley was talking about. It’s hard to predict how innovation will change the market behavior and change the market size in future.

Second, the Internet changes how distribution happened. The Internet made the cost of distribution zero for companies with a good install base, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s hard to predict the market size of Internet-era companies. Uber as a ride-hailing business is x, but add delivery to it, it becomes 3x. Add self-driving to it, and it becomes an entirely different story. When it launched food delivery, it didn’t have to burn money like it did in it’s early days to acquire customers. It could rely on it’s current customer base to start ordering food.

And these two reasons make market estimations and valuations tricky for founders, PMs and investors. So what does it lead to, besides the challenge?

It leads to certain behaviours that we see in founders and investors of the tech companies.

You will see the large ambition from startup founders is rewarded heavily by the market, because that is the first step to take the company to a much larger market and win there. The possibility of this happening is higher for the Internet companies in absence of the distribution moat. The history of the Internet companies is full of such examples.

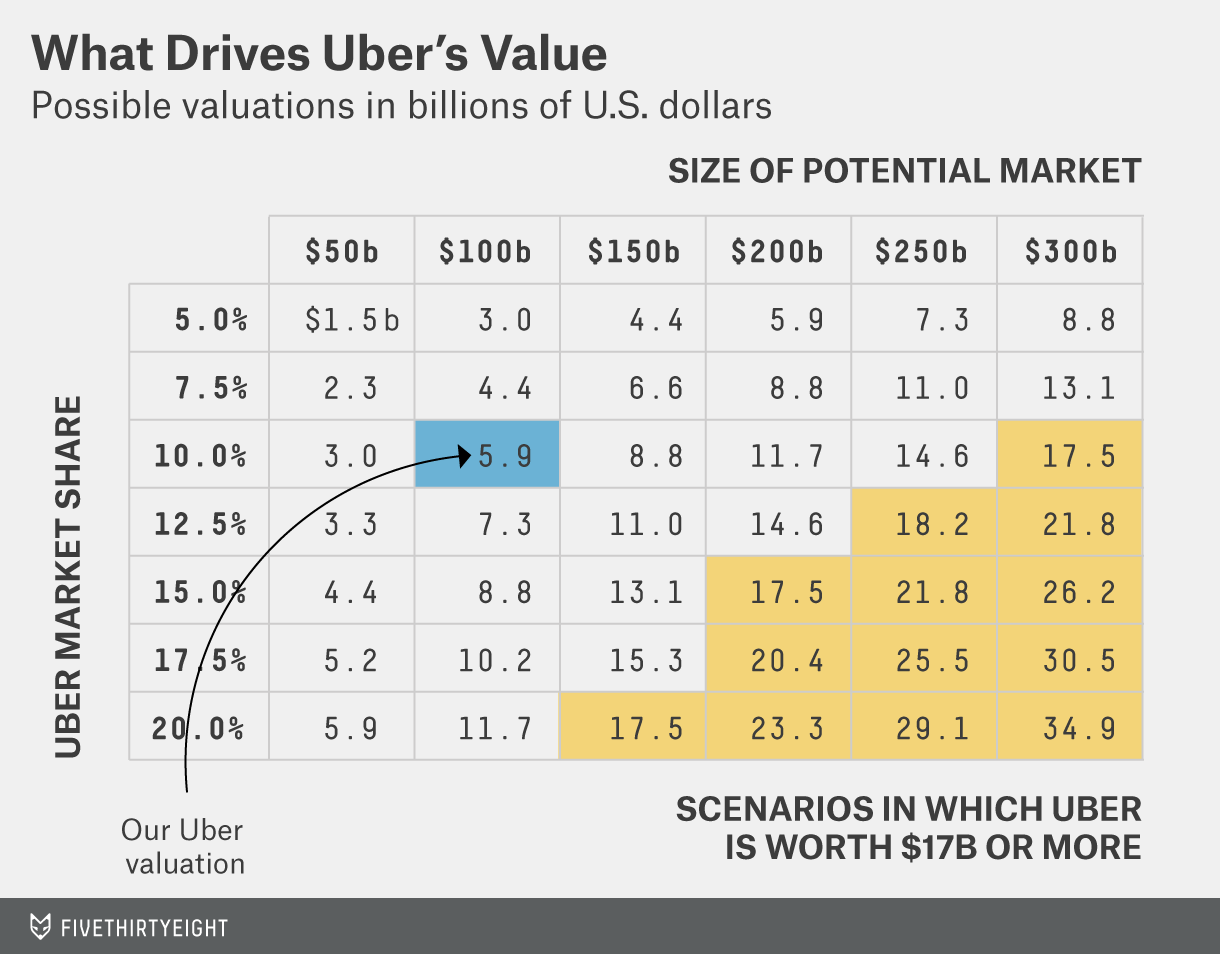

In absence of a distribution moat, the market rewards innovation heavily because that can help a company win the market. That reflects in tech companies investing heavily in R&D. Meta and Nvidia invested 30% of their revenue in R&D in 2022. Compare it to Pepsico, which invested just 1% of it’s revenue in R&D.

What Can Product Leaders do?

One of the most useful aspects of market sizing for product teams is also the ones least talked about — confirmed market size. A confirmed market is where the PMF of the product is confirmed! From the TAM, you need to filter out segments where the PMF isn’t there. For example, if the PMF lies in the online, women only audience for a fashion retailer. Use that as the filters to get to confirmed market.

The confirmed market size can be calculated by the total size of confirmed market, multiplied by the share a company can achieve.

A discussion around the confirmed market can lead to few good things for product teams:

Helps predicting growth and growth plateaus consistently — Imagine that you know that you have PMF in urban, k-12 teachers for an app built for classroom. You have already taken a huge chunk of market share and are saturating. While building the strategy for next year, you would be cautious to put high growth for the core app, and also push the team to plan out the next market to explore and move into.

Finding adjacencies to grow into — The benefits of knowing your confirmed market is that it becomes easy to figure out your adjacent markets. Adjacent markets take less time and energy to get into and capture.

And don’t forget, innovation expands the TAM, and so does getting into new markets where distribution advantage is there.

To summarise,

It’s hard to predict how innovation will change the market behavior and change the market size in future.

Internet made the cost of distribution zero for companies with a good install base, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s hard to predict market size of the Internet era companies.

The large ambition from startup founders is rewarded heavily by the market, because that is the first step to take the company to a much larger market and win there. The possibility of this happening is higher for the Internet companies in absence of the distribution moat.

In absence of a distribution moat, the market rewards innovation heavily because that can help a company win the market. That reflects in tech companies investing heavily in R&D.

As a product leader, you can use confirmed market size to predict growth and saturation. You can also use it to find adjacent markets.

We will end this post with the question I posted on LinkedIn around MVP this week.

The LinkedIN Question

I posted the following question with options on LinkedIn this week.

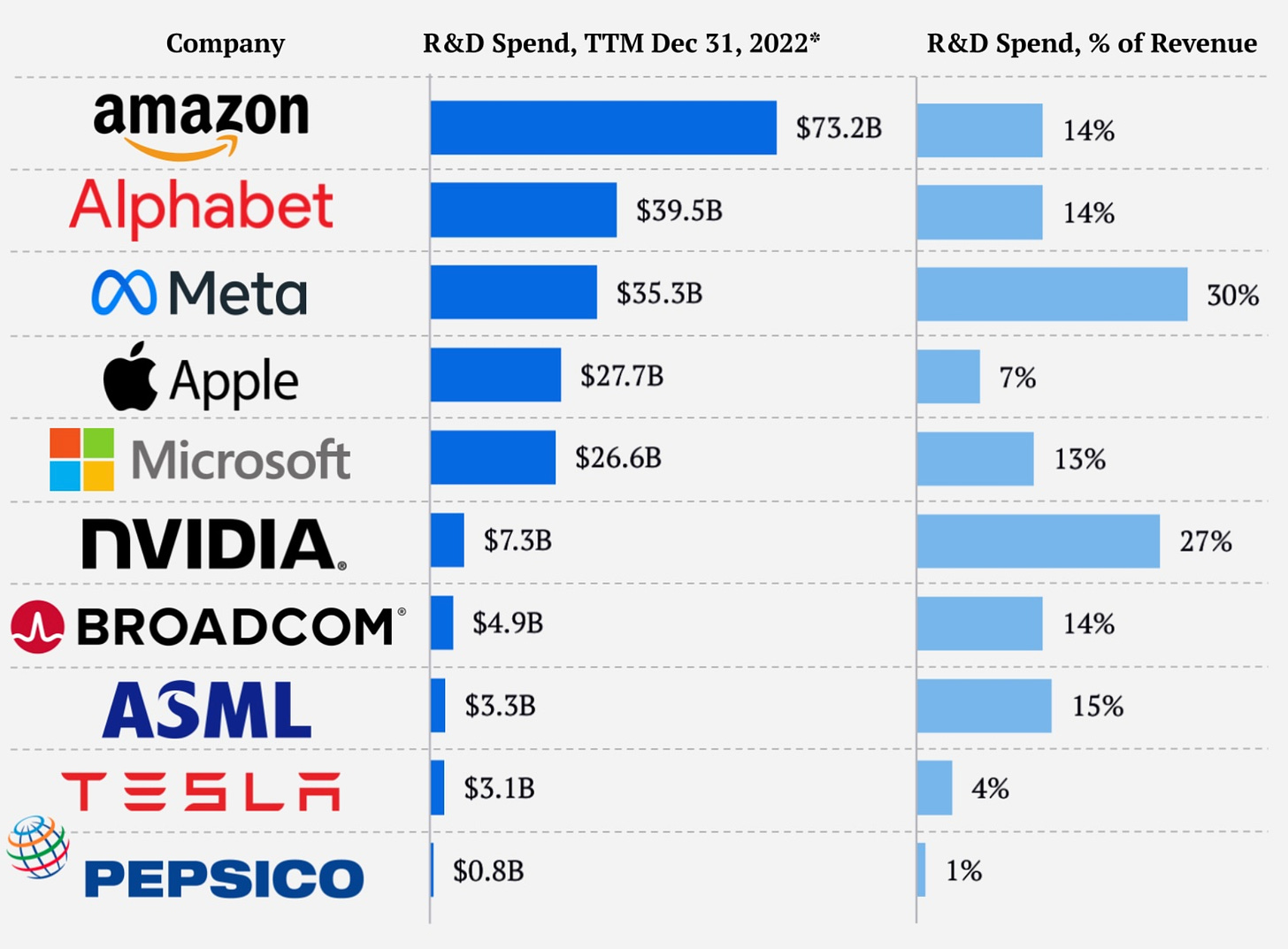

The audience is pretty split on this one, and here is my response.

MVP and MLP are hard to distinguish. After all, if you create value through your MVP, users will come to love it.

Most of the MVP designs have an objective to test the riskiest hypotheses — be it around customer needs, usage patterns, or business model. MVP is equivalent to Riskiest hypothesis testing. If you aren’t thinking about the risks while designing MVP, you are doing it wrong.

Experimentation and MVP are two separate things. Experimentation (a/b testing) is what comes after you have launched MVP.

So experimentation is the correct option.

Thank you for reading :)

If you found it interesting, you will also love my

I love and respect what you are doing. I wanted to ask a question though. We talk about startups and stories from the US. When and how will we start talking more about startups and stories from the Indian ecosystem?

Hi Deepak,

I have one question on this point: In absence of a distribution moat, the market rewards innovation heavily because that can help a company win the market. That reflects in tech companies investing heavily in R&D. Meta and Nvidia invested 30% of their revenue in R&D in 2022. Compare it to Pepsico, which invested just 1% of its revenue in R&D.

Meta does have distribution moat right ? Can you please explain this better.

Thanks.